Portraits in the manner of William Adolphe Bouguereau, French, 1825-1905

Landscapes in the manner of Jan Van Der Heyden, Dutch, 1637-1712

Paintings in the manner of

Inspiring Smiles Forever

Complete Works, Portraits, Landscapes, Still Lifes, Sculpture, Lego Artist...

Click To Sign up for auction notices or check EBTH & E-Bay

Have any Tom Lohre painting on a myriad of materials via Fine Art America

If you don't see your favorite painting request it to be offered.

Post comments on Sidewalk Shrines and Noted Icons https://www.facebook.com/artisthos/

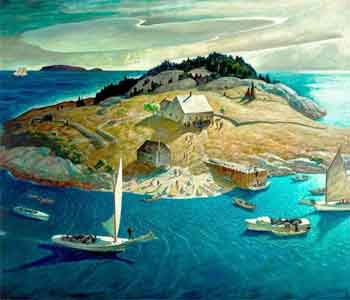

NC Wythe's Island Funeral

Detail of Helen Feeding the Ducks

It is special to see your own technique in NC's work. The transparent manner in "Island Funeral" seems to indicate he worked transparently with maybe egg tempura or casein tempera. Painting transparent paintings relies on how long you have to work the surface until the paint starts to dry. Then you have to give up until the surface is very dry to go back over. In the past I used stand oil, Damar varnish and a few drops of oil of clove to give me about 18 days working the surface till it started to set. Now I use castor oil and powered pigment giving me about a month of working time. The other unique aspects of this painting and my own is the use of a rubber brush or nip to remove the transparent paint revealing the white gessoed surface. I learned about the rubber brushes about ten years ago and now use them to the same effect of NC. In this painting you can set numerous time where he removed paint to highlight instead of using white paint. The whole reason is to achieve a luminescence quality that cannot be achieved with opaque paint.

N. C. Wyeth: New Perspectives

February 8–May 3, 2020 | Fifth Third Gallery

Taft Museum of Art

316 Pike St, Cincinnati, OH 45202

Co-organized by the Brandywine River Museum of Art in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, and the Portland Museum of Art in Maine, this exhibition showcases approximately 50 large-scale paintings by N. C. Wyeth (1882–1945), the patriarch of one of America’s most prominent artistic families. Many of Wyeth’s grand images bring to life the stories of Treasure Island, The Last of the Mohicans, and The Boy’s King Arthur—books published as part of Charles Scribner’s Sons Illustrated Classics series that are still well-known today. Despite his fame as an illustrator, however, Wyeth deserves much greater appreciation for his little-known fine art paintings. Thus, New Perspectives revises his reputation by also highlighting his private work, which reveals Wyeth’s love of nature and the contemporary American scene.

Watercolor portrait of patron as Ahab in Mort Drucker's parody of Moby Dick in MAD magazine.

Another great influence in Tom's life has passed away, Mort Drucker, celebrity cartoonist for MAD Magazine. He was 91. In classic Lohre style hesubstituted a collectors face for Ahab's in Mort's parody of Moby Dick for a xerox copy of the movie parody, couldn't afford the actual comic. This was the beginning of his water color manner using Mort and Thomas Rowlandson, British 1780 cartoonist, to direct him. Mort's big thick book was always too expensive. He has a two hour class on video that Tom has never been able to get a copy of. Schoolism did offer it but took it down. Tom's watercolor portrait manner peaked with a series of watercolors of his partner's mother who suffered from Alzheimer's for twenty years. Here she is with her teddy bear.

In Mort's Own Words

Caricature has usually been thought

of as negative art. Distortion can be negative, but I look for humor and positive

aspects. I try to find the personality of the character. Beyond the face, I

attempt to capture the movement and attitude of the body, and in some instances

the way that character dresses. Sometime my assignment will dictate the liberties

that I can take with a personality. My approach can range from a realistic,

detailed portrayal to simplified, humorous distortion. In doing a caricature,

it is possible to arrange the

features and overall shape of the head in two or three totally different ways,

and yet capture the personality in each drawing.

I was very fortunate growing up. My parents were behind me in anything I wanted

to do. Their first concern was my happiness, and I was always encouraged to

develop my talents. When I was very young, a teacher advised my mother that

I had a talent fordraw-ing and said that I should be encouraged to fulfill my

potential.

I remember, at age seven, in grade school, myself and another boy were the only

artistsin the class. Our project was to do a Thanksgiving Day mural around the

room. The other boy could only draw faces going in one direction so he had to

start at one end in order to meet me halfway. I had to begin at the other end

and work backwards since I could draw in either direction.

It has always been my ambition to be versatile and not be dependent on one person

or one company. I wanted to spread my abilities among many different areas and

not be dependent on one group. So much of my comic book art was a marvelous

learning experience, that I was able to become versatile. The remarkable aspect

of the comics was that as an artist, you could do action — regardless of the

genre. It was almost like being a movie director in discovering how to tell

a story, how to keep the interest of the reader's eye through close-ups and

long shots and dramatic lighting. I learned a lot from using all of those different

techniques.

Nick Maglin was one of the screeners at Mad, and I laid out my work for him,

and the looked it over. He brought my work into Bill Gaines's office. Nick came

out of the office and asked me to come in and meet Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein,

who were the publisher and editor of Mad. It was during the Yankee-Dodgers World

Series, the Subway Series of 1956. Bill Gaines was a Dodgers fan, and he and

Al Feldstein were listening to the game on radio. Gaines said, 'If the Dodgers

win this game, you're hired.' I've been working for Mad ever since.

I always felt that a large part of the success of Mad back in the early days

was that someone could read this magazine three or four times and still see

something new. It was a labor of love for me, and I was learning a lot from

it. Of course, I was always a big fan of the movies. I admired the actors and

actresses of the forties and fifties because they each had a personality. Each

one was different, and they were all great. Their look was different, their

body language was pronounced, and they were fullfledged actors and actresses.

Their uniqueness made them easier to satirize. I normally find it more difficult

to draw very pretty people, women with no distinguishable features and handsome

men who are cut out of the Arrow shirt mold. You need a personal characteristic

to latch onto. That means either a high forehead, protruding ears or some other

distinctive quality. You try to capture the spirit of a personality as well.

There's also a body language inherent, and I think it's important to capture

each detail to draw an accurate caricature.

The reason I chose both of the 'Oddfather' stories is that I was intrigued by

Mario Puzo's book. I was most interested in the segments that took place in

the early 1900's. I think I created some of my best art on those two stories.

In my early days, Mad was a showcase for my work. Mad has been successful for

thirty-five years, and influenced the writers of television monologues, nightclub

acts and advertising, and so many other areas of entertainment. To sustain a

magazine for that long with no outside advertising is a testament to its staying

power. What's also interesting is that Mad can communicate our culture through

translation. It's been all over the world, England, Germany, Israel and the

Scandinavian countries. Each individual country does their own translation,

worldwide.

Above all, Mad allowed me the artistic freedom to develop and grow. Al Feldstein

gave me that opportunity first, and I'm still experiencing that freedom and

encouragement under Nick Meglin and John Ficcara, who have since taken over

the editorial department. I love what I do for Mad, as it , gives me an opportunity

to think and do sight situations panel by panel. That's why, thirty years later

I still enjoy working for Mad.

The JFK Coloring Book became a huge success. It sold for two dollars a copy,

mainly to adults. Bookstores everywhere had copies of The JFK Coloring Book

opened to different pages in their display windows. It was unbelievable as it

had been so difficult to get a publisher interested in the book originally.

It was such a thrill to walk down the street and see what we had created being

openly promoted.

I keep an extensive file of personality photographs, because very often I need

extra photos of those same people later on for another assignment. If I didn't

build up a file for myself, I'd be at a terrible disadvantage. When I have to

do a caricature, I have to really know what the person looks like, front and

sideways. You can look at someone from the front, and you will never draw them

accurately in profile based on what you see. If you have the side view, in addition

to the front, then you can caricature the person correctly.

When I began my art career, I had no idea that I would cross cultural boundaries.

To know I was of help in one person's life is the greatest reward that I can

receive as an artist.

In regard to my work, it never ceases to amaze me that I am recognized and appreciated.

I'm very competitive, but not with anyone else but myself. When I'm working,

I feel many emotions. Every time I sit down to start a new assignment, that's

when the adrenalin begins flowing. I'm always trying to complete a piece of

art that makes me happy.

Four Lessons taught at the The Cincinnati Woman's Club

The first one was painting a portrait of Jesus by discovering his features by his traits.

Books:

Amazing Face Reading by Mac Fuller, J.D.

Face Reading by Chi An Kuei

The Face Reader by Patrician McCarthy

Face reading or physiognomy is a fascinating technique where you interpret

a person’s personality traits, fate (past, present, future), as well as

health condition – just by studying the face! You can do facial readings

on yourself, your lover, family members, friends, co-workers etc. and discover

things that may surprise you!

Face reading or physiognomy, is an ancient art of analyzing a person’s

character based on their facial features. Every facial feature – such

as narrow eyes, big nose, long chin, thick eyebrows etc. – has a psychological

meaning. You see, facial features and personality traits – such as gifts,

and talents – go hand in hand. Face reading is more than just learning

about a person’s characteristics. It can also give you a general idea

about your fate: past, present, and future. It is possible to actually see how

a person’s life will turn out – starting from their childhood until

their transition – just by reading the face! You can also do a face reading

to reveal the state of your health. The Taoist monk healers used to read faces

in their diagnostic practices. They discovered that since the skin is very thin

and delicate on the face, the first signs of any health problems will be revealed

in that specific area of the body. Today, practitioners of Traditional Chinese

Medicine (TCM) are still practicing face reading to detect illnesses in a patient.

Judy as woman in Bouguereau, 16" x 20", Traditional academic manner, Portraits, Traditional

Click image to see larger image

Teaching at the Cincinnati Women's Club

Bouguereau at Work 1825-1905 http://www.realcolorwheel.com/Bouguereau.htm

William Bouguereau at Work, by Mark Steven Walker

"William Bouguereau 1825-1905, is the Classical Painting technique, High

Art Painting in the history of man, Don Jusko."

To fully appreciate the art of Bouguereau one must profess a deep respect for the discipline of drawing and the craft of traditional picture-making; one must likewise submit to the mystery of illusion as one of painting's most characteristic and sublime powers. Bouguereau's vast repertory of playful and poetic images cannot help but appeal to those who are fascinated with nature's appearances and with the celebration of human sentiment frankly and unabashedly expressed.

But it remains to understand, given Bouguereau's in many ways unique style, exactly what the artist was trying to represent. Although Bouguereau has been classified by many writers as a Realist painter, because of the apparent photographic nature of his illusions, the painter otherwise has little in common with other artists belonging to the Realist movement. Bouguereau himself regarded his tastes as eclectic, and his work indeed exhibits characteristics peculiar to Neo-Classicism, Romanticism, and Impressionism, as well as to Realism. Within these categories, the painter is perhaps best understood as a Romantic Realist, but one would also be quite justified in this case in devising an entirely new school of painting and labeling him the first, the quintessential Photo-Idealist. The designation is apt in that, although Bouguereau actively collected photographs and tempered his observations of nature with a keen awareness of the qualities of light inherent in the photographic image, he almost never worked from photographs. The rare exceptions are a few portraits, usually of posthumous subjects, which are readily identifiable as photographic derivatives as they exhibit an uncharacteristic flatness and pose.

Bouguereau and his fellow academicians practiced a method of painting that had been developed and refined over the centuries in order to bring to vivid life-imagined scenes from history, literature, and fantasy. The process of acquisition of the skills necessary to produce a first-rate academic painting was a long and laborious one. Forever distrustful of educational reforms, Bouguereau once wrote:

"Theory has no place.., in an artist's basic education. It is the eye and the hand that should be exercised during the impressionable years of youth .... It is always possible to later acquire the accessory knowledge involved in the production of a work of art, but never - and I want to stress that point -- never can the will, perseverance, and tenacity of a mature man make up for insufficient practice. And can there be such anguish compared to that felt by the artist who sees the realization of his dream compromised by weak execution?"

The singular goal of traditional art instruction was to endow artists with the skills essential for the convincing pictorial actualization of their imagined visions. The croquis, figure drawings, compositional sketches, color studies, and cartoons were all logical steps in a process that at the end magically congealed separately studied details into an impressive, Illusionistic, and unified ensemble. Plein-air studies were also commonly done as part of the training of most academic painters. The impressionist landscape painters, deeply stirred as they were by the visual world, limited themselves to this genre, and succeeded in refining certain techniques that wonderfully rendered out-of-door effects; these techniques were later adopted, in some measure, by many studio painters as well.

Although broken color was not an innovation of the Impressionists (Vermeer was well aware of the principle), some of them took the technique to its presumed theoretical limit. But they did so at the expense of form and modeling, which continued to concern academic painters as well as conservative Impressionists such as Degas and Fantin-Latour.

Even the Realist painter Courbet, who professed disdain for the unseen worlds of the academicians, painted imagined scenes which he could not possibly have produced from direct observation; for their realization, he was perforce obliged to draw upon the traditional methods of the Academy.

The idealizations of Bouguereau's imaginary universe, which have delighted some critics, have incurred the wrath of others. Although some of the latter have loudly lamented the over-romanticized image of the French peasant presented by the painter, few of them have bothered to contemplate the heroic attention required to sustain such a vision of perfection in a less than perfect age. Moreover, as Bouguereau's contemporary Emile Bayard observed:

"It is good to note, in any case, that dirt and rags are not exclusive to the underprivileged and that indigence is not always clothed the same way."

A similar charge often leveled at Bouguereau is that his art bears little or no relationship to the realities of political, industrial, and urban life in nineteenth-century France. But if Bouguereau's art ignores in its content the pressing issues of the day, it may very well be because the artist, though well aware of them, nevertheless prompts us to lift our eyes from the ground and focus upon the lures of distant Arcadia; when misery is afoot, to exalt the more pleasant possibilities of la vie champetre is not artistic falsehood.

If one pronounces Bouguereau to have been out of step with his time, what must one then conclude about the many, many critics and collectors and viewers who supported him and others of a similar artistic persuasion? Could he really have achieved such prominence and financial success by going against the grain of the "realities" of the nineteenth century? Exactly what are those realities and exactly what attitude was a visual artist obligated to take toward them? If the accomplishments of Bouguereau are poorly understood today, that may have something to do with the shifting of aesthetic expectations over time. As for Bouguereau's public, it was a public raised on Raphael, a public that had not yet been conditioned to prefer abstract ideas to the palpable images that give them utterance, a public that insisted upon an obvious narrative content and that saw in Bouguereau someone opposed to the trends it regarded as inimical to art. It may very well be that a determining factor in Bouguereau's success as a painter, apart from his talent, was that he allied himself to that sizeable, conservative, and revisionist element of French Roman Catholicism which, under the aegis of such men as Louis Veuillot, popular theologian and publisher of L'Univers, refused to yield to the attacks on traditional ideals that were current at the time. Be that as it may, other writers have moved beyond a simplistic view of the question and have forcefully argued that Bouguereau properly belongs, for better or worse, in the nineteenth century; Linda Nochlin has noted, for example:

"...The very concept of contemporaneity is a complex one .... One might, as the great mid-nineteenth-century historian, Hippolyte Taine, implied, be perfectly justified in saying that the admonition to be of one's times was unnecessary, since artists and writers, whether they would or not, were inevitably condemned to being contemporary, unable to escape those dominating determinants which Taine had divided into milieu, race and moment. Thus the works of such strivers after eternal verity as lngres, Bouguereau or Baudry seem inevitably nineteenth century?."

The quality of reverie that is present in so many of Bouguereau's works shows clearly to what extent the artist's romantic disposition prevailed in concert with his classical forms. Bouguereau's alchemical transformations, in which objects, costumes, and the like are removed from the realm of the familiar and transplanted in a distant, archetypal and poetic world, continued a practice with a long academic tradition perhaps most famously articulated by Poussin. Robert Isaacson has observed: "It is noteworthy that Bouguereau tried in every way to avoid signs of contemporary life, even in his choice of costume (a timeless 'peasant' dress), setting the scene in a never-never land of pure beauty."

The craft of picture-making as practiced by Bouguereau basically followed the principles of academic theory as codified by the seventeenth-century aesthetician Roger de Piles. The code embodied the fundamental idea whereby a painting could be judged logically and objectively by its conformity to ideals established for its divisible parts, which were determined to be: composition, drawing, color harmony, and expression. The method Bouguereau used to execute his important paintings provided ample opportunity for the study and resolution of problems that might arise in each of these areas.

The separate steps leading to the genesis of a painting were:

1. croquis and tracings;

2. oil sketch and/or grisaille study;

3. highly finished drawings for all the figures in the composition, as well

as drapery studies and foliage studies;

4. detailed studies in oil for heads, hands, animals, etc.;

5. cartoon; and, only then,

6. the finished painting.

Evidently Bouguereau was constantly making croquis or "thumb nail sketches;" often these preliminary studies were done during meetings at the Institute or in the evenings after supper. For the most part they were scribbled from the artist's memory or imagination, others were sketched directly from nature. These drawings, hitherto unknown to the public, constitute a very important element of Bouguereau's work. For one thing, they yield a wealth of information about the artist's method. They also show in many cases how a particular composition evolved. Executed either in pencil or ink, they served as a means of determining the grandes lignes, the important linear flows and arabesques, within the entire composition and within individual figure groups as well. They were often refined by means of successive tracings.

The oil sketches, grisailles, and compositional studies in vine charcoal served as means for determining appropriate color harmonies and for the "spotting" of lights and darks. Like the croquis, these were usually executed from imagination and yielded a fairly abstract pattern of colors and greys upon which the artist would later superimpose his observations from nature.

The figure drawings represented the first important contact with nature in the evolution of the work. Among the considerations of the artist at this point were anatomy, pose, foreshortening, perspective, proportion and, to some degree, modeling. Although Bouguereau was reputed to have the best models in Paris, some of them were not always the most cooperative; as one observer noted:

"Bouguereau's Italian model-women are instructed to bring their infant offspring, their tiny sisters and brothers, and the progeny of their highly prolific quarter. Once in the studio, the little human frogs are undressed and allowed to roll around on the floor, to play, to quarrel, and to wail in lamentation. They dirty up the room a great deal -- they bring in a great deal of dirt that they do not make. They are neither savory nor aristocratic nor angelic. But out of them the artist makes his capital. Sketchbook in hand, he records their movements as they tumble on the floor; he draws the curves and turns of their aldermanic bodies, and he counts the creases of fat on their plump thighs as Audubon counted the scales on the legs of his hummingbirds."

If a particular figure was to be clothed, Bouguereau would also make drapery studies by posing a mannequin in place of the model and experimenting with the folds of cloth until a disposition was found that enhanced the underlying forms. Sometimes, especially for small or single-figure paintings, Bouguereau drew the model already draped. Most of the figure drawings were executed in pencil or charcoal (or a combination of the two) and were often heightened with white. The support for them is usually a heavyweight toned paper Of medium grain; such a background allowed Bouguereau to dispense with the problem of rendering troublesome half-tones which, in any event, were more easily and accurately realized in the painted studies.

Some of Bouguereau's comments help us understand the manner in which he perceived nature and its representation in his art:

"Paint as you see and be accurate in your drawing: the whole secret of your art is there."

"If you want to draw and model effectively, you have to see all of the details as well as the whole at the same time."

"One of the more useful tricks for getting the overall feeling of a painting, is to blink your eyes while looking at the model."

Some of Bouguereau's drawings were rendered with the aid of an optical device known as the chambre claire. This instrument, by means of prisms, allowed the tracing of a subject's outlines, as observed by the artist, directly onto a drawing board. Used as an artist might use a photograph today, the chambre claire permitted the artist to readily and quickly reproduce certain details of nature which could be used later in the studio as details in a painting.

The oil sketches of heads and hands (cat. no. 128), done, like the figure drawings, from nature were worked to such a degree of finish that Bouguereau was frequently able to use them for the finished painting without further recourse to the live model. The execution and the function of these studies have been described by Leandre Vaillat:

"Bouguereau would draw [these faces] quickly, in a four-hour session; he would then keep them by his side while working on the figures to which they belonged in the painting they were part of, and for which he had composed a well-balanced sketch beforehand.''

Emile Bayard on Bouguereau:

"He sketches broadly with an extraordinarily unerring eye and hand, completing a "piece" at one sitting, with no retouching, and painting a life-size figure in eight days at the most.

The ease of Bouguereau's execution was, to some degree, made possible by the thorough observations and notes contained in the preliminary studies.

"This impeccable painting, in which everything is depicted with the utmost care, where the slightest detail is lovingly rendered, was not easily achieved. The material execution was confident and rapid, but the preparations were lengthy and carefully thought out, each subject being weighed and looked at every which way with the help of studies, full-size cartoons, and numerous painted sketches."

When asked by a journalist if he worked quickly, Bouguereau replied:

"That depends. I produce a lot because I work all day long, without any breaks. It is the only way in fact of achieving good work. Often I find the desired gestures for my figures immediately; in that case, my painting is quickly completed. If, on the other hand, things don't go the way I want, I put the canvas aside for a day or two and wait till I feel better disposed. I never work on one picture only but have three or four in progress in my studio; that way, if a model doesn't turn up one day, I don't have to sit around with my hands in my pockets, I can work on the others.''

Bouguereau's medium is described by Moreau-Vauthier:

"Bouguereau used siccatives in his painting: a first siccative, a kind of Courtrai, employed by house-painters and known as siccatif soleil; and then a second, mysterious siccative whose recipe he kept secret. However, one of his pupils believes it was composed of a mixture of "siccatif de Haarlem" and essence, plus a little oliesse added in the summer months to prevent its drying too quickly. As with most painters, Bouguereau changed methods several times. One of his students wrote me: "Bouguereau, at the time I entered his studio, used as his sole medium a liquid composed of Courtrai mixed with nut oil and turpentine oil in varying proportions, depending on the colors used. Thus, for shadows, [he used] spirit and Courtrai, with little or no white; for the other colors, oil, spirit, and a small amount of Courtrai; finally, to rework a dry outline, pure or nearly pure oil or spirit. He oiled out the area to be re-painted to desemboire [that is, to treat the canvas so as to prevent the color from sinking in] it, with either the first or the second liquid, depending on the effect he wanted. He also painted with picture-varnish blended into these two liquids, but that was before I entered his atelier .... "

Bouguereau used "siccatif soleil" in order to lay in his sketch without thickening it. Sometimes he left it to dry before re-working; other times, he repainted over it immediately, using a second, less powerful siccative [the secret one]. In the case of a dry sketch, he rubbed this same siccative in before re-working. He has also painted with picture-varnish. In short, he painted with a medium that dried right under the brush."

The "secret recipes" described by Moreau-Vauthier conform closely to several found in Bouguereau's sketchbooks; they are as follows:

1864 [Sketchbook No. 22]

Quantities for the paste:

Siccative of Haarlem, 6 drops, Diluted with turpentine Oil 2-3 drops oil, as needed. Courtrai, 1 drop. Add some Haarlem to the white and one drop of Courtrai to the other colors.

Glazing:

Oil and spirit, little Haarlem. For an extra glaze, little or no turpentine.

1879 [Sketchbook No. 1]

To prime the canvas before painting:

Haarlem, picture-varnish diluted with elemi (little elemi, 1/5), a drop or two brown fixed oil and terebine. Afterwards paint with the same mixture diluted with a few more drops of fixed oil and terebine ..

Other dipper:

picture-varnish and elemi in small quantity and light fixed oil diluted with turpentine. For a fresh glazing, add to the 2nd dipper a few drops petroleum spirit.

1894 [Sketchbook No. 2]

To prime the canvas before painting:

Haarlem, picture-varnish diluted with a little elemi at 1/5, one or two drops fixed oil and terebine.

1st dipper: for painting, same mixture plus a few more drops fixed oil and terebine.

2nd dipper: picture-varnish and elemi in small quantity and light fixed oil diluted with turpentine.

3rd dipper: for a fresh glazing, add to second dipper a few drops petroleum spirit.

1894 [Sketchbook No. 2]

Under painting. Copal dissolved in turpentine diluted with elemi (little).

Ist dipper, for painting: White siccative. Oliesse and elemi.

2nd dipper, for glazing: Turpentine oil (ratafia caron), oliesse, petroleum spirit.

Venetian-type painting

1) grind pigments into turpentine;

2) add part of the oliesse and grind again;

3) at the last minute, add the Robertson paste [a commercially prepared medium]

and give a final grinding. Very good for all lacquers.

Bouguereau never mentions a specific palette, but Moreau-Vauthier is again

helpful in this regard; he gives it as:

Naples Yellow (lead antimonate)

Yellow-Ochre

Chrome Yellow, dark

Viridian

Cobalt Blue

White Lead

Light Vermilion

Chinese Vermilion

Mars Brown (iron oxide); this available from Lefranc & Bourgeois Van Dyck

Brown

Burnt Sienna

Ivory Black

Bitumen

Genuine Rose Madder, dark

All of Bouguereau's colors are still available today as prepared artist's paints, but not from any single manufacturer. In one of his sketchbooks, Bouguereau lists so many pigments that no palette could possibly contain them, but it is interesting to note all the possibilities he had to choose from.

1869 [Sketchbook No. 5]

Manganese oil -- Leclerc, rue St. Georges...

White lead, (Silver White) Lead carbonate

Ivory Black, Charred Ivory

Minium, Red Lead

Vermilion, Mercuric sulphide

Brown Madder, Iron (charred) Cassius Red, Tin bioxide and gold protoxide

Iodine Scarlet, (English)Mercuric iodine

Purple Red, Mercuric chromate

Madder Lake,

Mineral Yellow, (Paris) Oxi-chloride of lead

Charred Massicot, Lead bioxide and protoxide

Minium, orange, Charred ceruse (lead)

Chrome, Lead Chromate

Orpiment, (King's Yellow) Arsenic sulphide or Yellow sulphide of arsenic

Naples Yellow, Lead oxide and antimonate

Ochre, Hydrated ferric oxide

Indian Yellow, [?](It was a secret of W/N back than. The principal constituent

of Indian yellow is a mixture of the calciun and magnesium salts of euxanthic

acid.)

Prussian Blue, Iron protoxide sulphate and prussiate solution

Mineral Blue, Iron and [?]

Ultramarine Blue, Lapis Lazuli

Cobalt, Cobalt

smalt, Powdered cobalt glass

Ash Blue, Copper

Indigo, Vegetable

Violet, Charred iron peroxide Cassius, purple and alumina

Verdigris, Copper acetate

Scheele Green, Copper arsenate

Mountain Green, Copper carbonate

Chrome Blue, Chromium protoxide

Cobalt Blue, (mineral) Cobalt and zinc

Viridian, Sulfate of lime and copper aceto-arsenite

Green Earth, silica, iron oxide, potassium, magnesia carbonate and water

Sap Green, Unripe buckthom berries (lake)

Cassel Earth,

Cologne Earth, Natural earth darkened mostly with bitumen

Umber, Natural earth colored with ferric oxide, manganese dioxide plus a little

bitumen

Sienna, Ochreous natural earth and manganese(bioxide ?)hydrate

Prussian Brown, Charred Prussian Blue

Asphaltum, Bitumen

Mummy, Asphaltum and bone ash

Yellow Lake, Albumen colored with Avignon yellow grains

Cadmium, Cadmium sulfide

Azure or smalt, powdered cobalt glass

It seems that Bouguereau purchased prepared colors in tubes, but on occasion he also ground certain colors himself. It is not known precisely which brand(s) of prepared colors Bouguereau used, but he did write an endorsement for the colors of Lefranc: "I am pleased to have only good to say about the colors made by Messieurs Lefranc et Cie.''

It is surprising to see bitumen included among the colors on Bouguereau's palette, in that hardly any of his canvases exhibit the ravages that have afflicted the works of that substance's less prudent users. Bouguereau made the observation:

"Spirit of bitumen can be purchased on the rue de Buci, across from No. 14; it can be applied as is on the canvas and, for painting, mixed with Lefranc bitumen."

Moreau-Vauthier has written:

"I heard Bouguereau say that bitumen is safe if used only for superficial retouching and not in depth, for under painting." "Bouguereau resorted to bitumen for retouching, binding, and blending; he glazed with spirit of bitumen in scumbles and reworked the area in the glaze before the bitumen was dry .... To convince people of the sturdiness of bitumen, Bouguereau used to repeat: "They make sidewalks with it."

Bouguereau purchased his materials from many different sources but the most

important were:

Deforge et Carpentier -- 8 blvd. Montmartre

Hardy-Alan -- 1 rue Childebert, until 1868; later, 56 rue du Cherche-Midi Jordaney-

7 rue Brea

L'Aube (successors to Jordaney) -- 7 rue Brea

When painting, Bouguereau almost always made last minute changes, despite the extensive preliminaries and the fact that his original drawing was unalterably inked upon the ground. If one looks closely at The Education of Bacchus (cat. no. 100), numerous adjustments made in the final stages of execution become apparent; hardly a single figure has been left unmodified from the original plan. The obsession with perfection left the painter little peace:

"Starting a new picture is very pleasant, for you always believe that this time you're going to create a masterpiece; you take pains, and little by little the painting takes shape, the effect comes through. You feel marvelous sensations. When it's done, however, things are different. You want to touch up the arm, the movement of the body doesn't seem graceful.., and you end up doing nothing, for fear of having to redo the whole thing completely."

The finely modeled flesh tones in his paintings led many critics to accuse Bouguereau of relying too heavily on the badger blender. But according to Emile Bayard:

"There has been talk of badger-blending, which still amuses the artist, since he has never resorted to this technique ...."

Judging from photographs of the painter in his studio, Bouguereau appears to have used the standard round and flat white bristle brushes commonly used for oil painting (fig. 14). Lovis Corinth observed that the artist generally preferred wide brushes. He also used a palette knife for scumbling color into landscape passages and, for painting fine details, a mahl stick.

The glazed passages in the paintings are primarily limited to the darker portions, particularly backgrounds and drapery; conversely, the flesh tones are solid and achieve their translucence by means of careful modeling and precise observations of values and color notes. Richard Lack, a painter of "the other twentieth century" -- that is, a painter who continues to paint in the classical tradition -- has written:

"Alongside his mastery of line, Bouguereau utilizes tone relationships with commanding authority. Harmony of dark and light tones is of first importance in a painting. It is even more crucial than color since tone arrangement must underlie every color scheme. Color or hue cannot exist without value. Painters often say that any color scheme will suffice if the values are harmoniously conceived. Bouguereau's handsome value harmonies are like music of great beauty and subtlety .... An... ingenious use of light and shadow is seen in the celebrated "Nymphes et satyre" [cat. no. 51]. The figure grasping the left arm of the satyr is backlit with strong reflected light pouring into the shadow side of the head and shoulders, posing one of the most difficult problems for the draftsman. A head of this sort must be modeled with a minimum of tone contrast in order to oppose those passages in the light that are fully modeled. Once again, Bouguereau succeeds with consumate authority."

One of the most impressive features of Bouguereau's renderings is the manner whereby the artist expresses a maximum of form with a minimum of means. Passages that appear to be modeled with nearly fiat tones acquire volume through manipulation of contours and surrounding values.

The location of Bouguereau's first Paris studio is not known. But in 1866, the painter engaged the architect Jean-Louis Pascal to design his home and atelier at 75 rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, finally occupied in September 1868. Undoubtedly Bouguereau himself had an important hand in the planning of the workspace.

The new atelier occupied the northern half of the upper floor of the house and measured 11.5 x 9.5 meters (37 ft. 9 in. x 31 ft. 2 in.) with a ceiling height of 6.9 meters (22 ft., 71/2 in.) (fig. 15). The long northern wall of the studio was windowed from floor to ceiling and hung with heavy drapery in order to control the light. In addition, there was a skylight measuring 4 x 2.5 meters (13 ft 11/2 in. x 8 ft. 21/2 in.) in the exact center of the ceiling. The lower surface of the skylight rested flush with the ceiling and was composed of a wire-reinforced light-diffusing glass. Just under the skylight a roll of opaque fabric was suspended that, by means of wires and pulleys, could be extended along two guide wires in order to regulate the amount of light entering from above. Originally, a sizeable balcony projected from the central window; it was enclosed on all sides by glass so as to form a small greenhouse, which in no way did obstructed the light from entering the studio (fig. 16). The balcony, along with the glass enclosure, was dismantled many years after Bouguereau's death, and there presently remains only a narrow balcony and railing.

The interior of Bouguereau's atelier was painted a light, warm, twenty-percent grey which visitors described as "luminous". The journalist Paul Eudel has described a visit to the studio in 1888:

"At first glance, a real disappointment. No knickknacks, absolutely no attempt at elegance. No suits of armor and no Gothic furniture either. It is in no way a curio shop, like some sumptuously appointed studios that are fitted for everything except painting. Here, on the contrary, there is constant hard work ....

Seated in a corner, a cherubic pupil clutches a piece of cardboard on his lap and tries, with a still shaky hand, to reproduce the academic outlines of the bent head of Niobe, whose plaster mask hangs before him .... The whole length of the studio is divided by a partition about two meters high, covered with old, mediocre tapestries. Against the partition rests a fine ebony Louis XIV clock ....

Perched on the mirrored cornice, two stuffed birds gaze dejectedly at Duret's Chactas, which is made of plaster with a chocolate-hued patina and which, from afar, could be mistaken for Florentine bronze ....

At the foot of the walls, painted in a terra-cotta shade, lean portfolios crammed with drawings and sketches. On the floor, on shelves or hanging from nails, Greek and Roman casts ....

I catch sight of a real Chardin, not a painting but a natural Chardin: on a stepladder box lie three small pipes, a ruler, a yardstick, and a sample of varnish, "guaranteed resin-free," the bottle of which holds down its prospectus. It is a cosy room, unpretentious and very typical."

Bouguereau said of his atelier: "It is a workroom, that's all."

Elsewhere he described his work habits:

"Every morning I get up at seven without fail and have breakfast, then I go up to my studio which I don't leave all day. Around three o'clock, a light meal is brought in; I don't have to leave my work. I rarely have visitors, since I hate to be disturbed. My friends, though, are always welcome. They don't bother me, I can work even when it's noisy or while they're chatting. When I'm painting, I don't pay attention to anything else."

The artist usually spent August and September at his home in La Rochelle (15 rue Verdiere), where his schedule was somewhat more relaxed.

Marius Vachon has written:

"In a comer of the garden measuring some two hundred square feet, he arranged his outdoor studio; and in the orangery he set up his interior studio. At six in the morning, rain or shine, drizzle or wind, escorted by his three dogs and a servant, he sets out for a two-hour walk through the fields or along the seashore. Once home, he has a cup of tea and settles down to work. At eleven, the family gathers for lunch; at one, he resumes work with his model and continues until six in the evening, with a few short breaks.

Then the painter picks up his rustic cane and his soft-felt hat and leaves, a cigarette between his lips, like any ordinary bourgeois, for a walk around the harbor, to watch the sun set on the sea. When the town clocks chime seven, he goes back home for dinner; and at ten, it is curfew time. At dawn on Sundays, the master and his wife climb into a carriage to meet a childhood friend, an architect in a neighboring village, for an outing in the countryside or, during hunting season, to take a few pot shots, in his own words, "at hypothetical quails or the occasional rabbit."

Many of the paintings which Bouguereau began in La Rochelle were finished in Paris; usually all that remained to be done was the completion of the background. He wrote one October:

"I still have landscape elements to paint into my backgrounds and I am hurrying, fearing an early frost will leave only dry, leafless trees."

Bouguereau also produced certain paintings that do not belong to any of the categories described above. These works were clearly not made as preparatory studies and yet they often relate to important compositions. >From time to time, in addition, he made drawings or tracings of drawings to send to prospective clients interested in a commissioned work or a work in progress. The artist also made pen drawings for reproduction purposes, since halftone reproduction processes were both time consuming and expensive.

Bouguereau frequently painted "reductions" (sometimes Bouguereau refers to these as "reproductions") as well, which were simply smaller versions of important canvases. These works were finished to the same degree as the large versions; they were signed but never dated. Sometimes Bouguereau's students had a hand in the execution of the reductions; in 1877, he wrote his daughter: "Doyen... worked today on the completion of the reduction of Youth and Eros ...."

The reductions originally served as models for the engravers, who relied on them to make quality plates for reproduction purposes; in this way the sales of important paintings were not delayed by the engraving process, and the engraver was not encumbered by the bulk of Bouguereau's large formats. Bouguereau painted most of his reductions early in his career; the first one recorded is done for Charity, in 1859. After that, reductions appear regularly and in great quantity; of sixteen paintings produced in 1867, eight were reductions. There are about a half dozen instances where two reductions of the same painting were made.

Such proliferation, of course, could only have been intended for commercial reasons. Neither Baschet nor Vachon recorded these early reductions with any consistency, but they are listed in the artist's account books.

But with time the painter seems to have grown weary of the practice, and after 1870 reductions appear on the average of about two per year and are usually limited to works from the annual Salon, destined for the engraver. The reductions either progressed at the same time as the large canvases or they were painted shortly after their completion; in any event, Bouguereau required the large canvas for the execution of the reduction. He explained to a correspondent:

"... You have not understood me. After telling you that I did not have the time, I told you that I was unable to do the reproduction of a painting I no longer had; this should have explained why I found it impossible to fulfill the commission .... I should also add that today I no longer do any reproductions other than for engraving purposes; that is because most of my paintings are too cumbersome for the engraver to work directly from them, so I am resigned to it. But it is always against my wishes.''

Most of Bouguereau's reductions appear to be faithful copies of the large canvases, but there may be a few exceptions. There is an engraving of L'Orage (The Storm), 1874, executed by Annedouche and published by Goupil, which was presumably done from a reduction (of which no photographic record has been found) and which has a completely different background from that of the large version. The small version of The Storm is specifically mentioned by Baschet as a "reduction pour la gravure" as opposed to simply "reduction."

A detailed description of Bouguereau's materials and procedures must not obscure the fact that it was above all the master's hand, eye, and temperament, rather than pure technique, that account for the ineffable quality of his work. For those who would invoke the painter's muse, Bouguereau left a final caveat:

"One is born an artist. The artist is a man endowed with a special nature, with a particular feeling for seeing form and color spontaneously, as a whole, in perfect harmony. If one lacks that feeling, one is not an artist and will never become an artist; and it is a waste of time to entertain the possibility. This craft is acquired through study, observation, and practice; it can improve by ceaseless work. But the instinct for art is innate. First, one has to love nature with all one's heart and soul, and be able to study and admire it for hours on end. Everything is in nature. A plant, a leaf, a blade of grass should be the subjects of infinite and fruitful meditations; for the artist, a cloud floating in the sky has form, and the form affords him joy, helps him think."

Bouguereau at Work

1. Bouguereau's collection of photographs was extensive and included prints by many of the best known photographers of his time as well as by lesser-knowns.

2. William Bouguereau, "Discours de M. Bouguereau" in Seance publique annuelle des cinq Academies du 24 October 1885, lnstitut de France, pp. 10-11.

3. R.H. Ives Gaminell, Twilight of Painting (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1946), pp. 66-67.

4. 12 mile Bayard, "William Bouguereau" in Le Monde Moderne (Paris: A. Quantin), December 1897, pp. 851-852.

5. Linda Nochlin, Realism (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1978) p. 104.

6. Robert Isaacson, "The Evolution of Bouguereau's Grand Manner" in The Minneapolis Institute of Arts Bulletin,, Vol. LXII, 1975, pp. 7576.

7. Anonymous, "First Caresses" in [?], from the files of the Joslyn Art Museum Library, Omaha, Nebraska.

8. Carroll Beckwith, "Bouguereau" in The Cosmopolitan, January 1890, Vol. 8. No. 3, p. 264.

9. William Bouguereau, quoted by Emile Bayard, p. 854.

10. William Bouguereau, Paris Journal, p. 19. Bouguereau Family Estate.

11. Ibid. p. 20.

12. William Bouguereau, "Allocution de M. Bouguereau" in Distribution des Prix de l'Ecole de Dessin au Grand Theatre, 1899, (Bordeaux, 1899), pp. 17-18.

13. Ldandre Vaillat, "Une resurrection de Bouguereau" in L'Illustration, 22 janvier 1921, p.' 64.

14. Jehan-Georges Vibert, La science de la peinture (Paris: Paul Ollendorff), 1891, pp. 324-325.

15. William Bouguereau, carnet No. 2, 1894. Bouguereau Family Estate.

16. In fact, Cennino Cennini mentions nothing about the incorporation of flour into the ground. Moreau-Vauthier's reference is surely the same as the one in Bouguereau's handwriting, found on a card inserted in Sketchbook No. 5, 1869 (Bouguereau Family Estate), to Giovanni Battista Armenini, Dei veri precetti della pittura. The relevant passage reads: Ci song molti che prima turano i buchi alle tele con misture di farina, olio ed un terzo di bidccd ben trita, e ve la mettonG su con un coltello... Bouguereau's notes from Armenin-i read as follows: farine-huile-blanc-ben trita iraprima, avec un 6e de vernis du vernis dans tous les glacis vernis huile d'abezzo claire - a petit feu huile de sasso etendu ti chaud mastic huile de noix (au leu) passe dans un linge pendam qu'il [?] un peu d'alun calcine et pulverise le rend plus brillant (le meler aux bleux, aux lapis qu'il fait secher)

17. Charles Moreau-Vauthier, Comment on peint aujourd'hui (Paris: Henri Floury, 1923), pp. 46-47.

18. Frangois Flameng, "Notice sur la vie et les travaux de M. Bouguereau," Seance du 24 fevrier 1906, Academie des Beaux-Arts, p. 16.

19. Camille Bellanger, cited in A. Lemassier, "Comment peignaient les grands peintres: William Bouguereau" in Peintures-Pigments-Vernis, I.)ecember 1962, Vol. 38. No. 12, p. 734.

20. Jerome Doucet, Les peintres francais (Paris: Librairie Felix Juven, 1906), p. 169. 21. Emile Bayard, cited in A. Lemassier, p. 733. 22. Frangois Flameng, "Notice...", p. 16.

23. William Bouguereau, quoted in "M. Bouguereau chez lui" in L'Eclair, 9 May 1891.

24. Ibid.

25. Siccatif de Courtrai" was a term applied to dryers of diverse quality

made by many different manufacturers, each of whom seems to have use a different

recipe. This lack of uniformity may well have been the real cause of the siccative's

bad reputation. Siccatif de Courtrai was made by heating linseed oil in the

presence of litharge and a salt of manganese. According to Ludovic Pierre, the

siccative, when used correctly, did not impair the longevity of a painting:

"It is a very powerful siccative when it is well made; it is also sufficient

to add it in small proportions to the color one desires to dry rapidly. We believe

that when used with the greatest moderation, it is not as delaterious as has

been suggested by some, but obviously one has to be cautious.

Its dark brown color.., looks like black coffee and tends to muddy lighter tones...

(Ludovic Pierre. Renseignements sur les couleurs, vernis, huiles, essences,

siccatifs et fixatifs employes dans la peinture artistique (Paris: Imp. F. Schmidt,

n.d.), pp. 100-101)" Bouguereau also mentions "huile grasse"

in some of his formulas. The substance seems to have been either Courtrai or

something very similar.

Again according to Pierre:

"Huile grasse a tableau" is linseed oil heated with a small quantity of lead and manganese products which render it very siccative (Pierre, p. 89). The fact that Bouguereau refers to it once as "huile grasse brune" would also lead one to believe that it was basically the same product as "siccatif de Courtrai." Bouguereau also mentions the use of "huile grasse blanche;" Pierre gives the following information: "Huile grasse blanche" is pure clarified poppy oil treated in a special way with certain siccative agents using a base of lead and manganese; it acquires siccative properties without becoming discolored. Thus it is sold under the name "huile grasse blanche." We can be no more precise as to its employ than we can for "huile grasse a tableau." It is never transparent, but always displays a somewhat milky appearance.

Pierre also gives a description of "Siccatif de Haarlem":

"Siccatif de Haarlem" was invented by M. Durozier the pharmacist, now deceased. We can do no better than repeat what he said himself about his product. This siccative replaces "huile grasse" and all the other siccatives using lead bases; it is characterized by its ability to preserve tones, inhibit "sinking in," and prevent cracking. It can be diluted with both oil and turpentine; it renders glazes solid and can serve as the final varnish when extended with rectified turpentine.

(Pierre, p. 101)

Products bearing the names "siccatif de Haarlem Duroziez [sic}" and "siccatif flamand" are still manufactured by Lefranc & Bourgeois; one of their brochures gives the following description: "Siccatif de Haarlem Duruziez": This painting medium is, like "siccatif flamand" made from a base of Madagascar copal resin. While it is less concentrated, it possesses the same characteristics. Besides the difference in color, it dries less rapidly than "siccatif flamand." (Les mediums pour les couleurs a l'huile [Paris: Lefranc & Bourgeois, 1982], h.p.). Ludovic Pierre comments on "siccatif flareand," which was also an invention of Duroziez:

..."Siccatif flamand" could be called the twin brother of "siccatif de Haarlem. "... in a technical sense, this product is not a true siccative, although it does facilitate drying of the colors to which it is added; it is composed of oil, turpentine, and hard copal resin. "Siccatif flamand" contains no lead and may be mixed with turpentine in all proportions without coagulating. it can be added to oil colors without fear of the colors altering as they age. It is only slightly colored and has no effect on light tones (Pierre, p. 102).

Hilaire Hiller gives the following information concerning oliesse:

A painting medium used by Gerome: Oil copal varnish mixed with Duroziez oil

- 4 parts

Rectified oil of spike or turpentine - 3 parts

Mix well by agitation, pouring the spike or turps on the copal-oil mixture.

Girardot said that this medium gave paintings "the solidity of flint."

The Duroziez oil is prepared by the firm of Duroziez of Paris, and it is known

by the trade name of Oliesse. (Hilaire Hiller, Notes on the Technique of Painting

(New York: Wastson-Guptill, 1969), p. 167, reprinted from the edition of 1934.)

26. Charles Moreau-Vauthier, Comment on peint aujourd'hui, pp. 37, 38, 63, 64.

27. "Terebine" is not to be confused with "terebenthine" (turpentine). Bouguereau notes: " Terebine sold at the color merchant, 3 or 5 Quai Voltaire, can replace, siccatif soleil, which in turn can replace siccative of Courtrai (Sketch book No. 2, 1894.) According to M. Henri Sennelier of Sennelier, 3 quai Voltaire, " terebine " was a" dryer made with American turpentine" (iiiore siccative by itself than its European conterpart). Apparently, terebine was a variation of "terebine francais" which contained one of several possible dryers, among them; resinate de plomb (lead resinate) linoleate de plomb (lead linoleate) linoleate de manganese (manganese linoleate)

It is probable that terebine was the same product known today as "Siccatif de Courtrai, blanc." Ludovic Pierre describes the latter: ...A siccative with a turpentine base which is extremely clear, almost without color, but which certainly has none of the siccative energy of true "Siccatif de Courtrai," for it dries the colors much less rapidly and does not harden them as well (Pierre, p. 101).

28. Charles Moreau-Vauthier, Comment on peint aujourd'hui, p. 24.

29. William Bouguereau, sketchbook No. 5, 1869. Bouguereau Family Estate.

30. William Bouguereau, excerpt from a letter published in Les peintres et la couleur (Paris: Lefranc, 1925), n.p.

31. William Bouguereau, sketchbook No. 2, 1894. Bouguereau Family Estate.

32. Charles Moreau-Vauthier, La Peinture (Paris: Hachette, 1913), p. 210.

33. Charles Moreau-Vauthier, Comment on peint aujourd'hui, p. 21.

34. William Bouguereau, quoted in "M. Bouguereau chez lui", n.p.

35. Emile Bayard, "William Bouguereau" in Le Monde Moderne, p. 854.

36. Richard Lack, Bouguereau's Legacy to the Student of Painting (Minneapolis: Atelier Lack, Inc., 1982), p. 4.

37. The birds served the artist as models for the plumage of his angels and cupids.

38. Paul Eudel, "Les ateliers des peintres: William Bouguereau", in L'lllustration, 30 June 1888.

39. William Bouguereau, quoted in "M. Bouguereau chez lui."

40. ibid.

41. Vachon, p. 99.

42. William Bouguereau, letter to Eugene Bouguereau, Paris 16 October 1886. Bouguereau Family Estate.

43. William Bouguereau, letter to Henriette Bouguereau, 22 July 1877. Bouguereau Family Estate.

44. These were for: The Elder Sister, 1863; The Prayer, 1865; Invocation to the Virgin, 1866; First Caresses, 1866; Covetousness, 1866; and Sleeping Children, 1868.

45. Sketchbook No. 32 (1861-1875), sketchbook No. 33 (1866-1886), and sketchbook No. 34 (1882-1894). Bouguereau Family Estate.

46. William Adolphe Bouguereau, letter to [?], 23 August 1871, La Rochelle. Collection of Mark Steven Walker.

47. Ludovic Baschet, Catalogue illustre des oeuvres de W. Bouguereau (Paris: Librairie d'Art, 1885), p. 51.

48. Vachon, p. 114.

Painting a Derived Work, 16" x 12", June 2, 2013

“To my mind, a picture should be something pleasant, cheerful, and pretty, yes pretty! There are too many unpleasant things in life as it is without creating still more of them.”

“Why shouldn’t art be pretty? There are enough unpleasant things in the world.”

“The pain passes, but the beauty remains.”

“I've been 40 years discovering that the queen of all colors was black.”

“There are quite enough unpleasant things in life without the need to manufacture more.”

“The work of art must seize upon you, wrap you up in itself, carry you away. It is the means by which the artist conveys his passion; it is the current which he puts forth which sweeps you along in his passion.”

“-last words about painting, age 78...

I think I'm beginning to learn something about it.”

“When I've painted a woman's bottom so that I want to touch it, then [the painting] is finished.”

“We are in a period of searchers rather than of creators.”

“You come to nature with all her theories, and she knocks them all flat.”

“If you paint the leaf on a tree without using a model, your imagination will only supply you with a few leaves; but Nature offers you millions, all on the same tree. No two leaves are exactly the same. The artist who paints only what is in his mind must very soon repeat himself.”

“One must from time to time attempt things that are beyond one's capacity.”

“The more they measure, the more they realize how much the Greeks departed from regular and banal lines in order to produce their effect.”

Quotes by Monet

"When you go out to paint, try to forget what objects you have before you — a tree, a house, a field. . . . Merely think, here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow, and paint it just as it looks to you, the exact color and shape."

The Art of Painting, From The Baroque Through Postimpressionism edited by Pierre Seghers in collaboration with Jacques Charpier from Hawthorn, Inc, 750 qC484 v.03, Library of Congress Catalog Number: 64-19203

Page 267 by Monet

ONE is born a painter, and if one is born for that, he always finds the way to express what he experiences, expressing it badly at first but finding the way himself. (Quoted by E. Hareux)

LANDSCAPE is but an instantaneous impression, whence comes that label they have given us, because of me, moreover. I had sent something I did in Le Havre from my window—sunlight in the mist, and in the foreground some boat masts pointing. . . . They asked me the title for the catalogue. It couldn't really pass for a view of Le Havre, so I answered: '' Put 'Impression.' " They made Impressionism out of it, and the jokes began to spread. (Quoted by M. Guillemot)

I paint as a bird sings.

The Art of Painting, From Prehistory Through The Renaissance edited by Pierre Seghers in collaboration with Jacques Charpier from Hawthorn, Inc, 750 qC484 v.01, Library of Congress Catalog Number: 64-13282

The Art of painting in the Twentieth Century edited by Pierre Seghers in collaboration with Jacques Charpier from Hawthorn

Painters on Painting Selected and Edited with an Introduction by Eric Protter by General Publishing Company, Ltd. 750.1 P148 1997, ISBN 0-486-29941-4 (pbk.),

Techniques of the Great Masters of Art by Chartwell Books, Inc 751.409 fT255, ISBN 0-89009-879-4

50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship, by Salvador Dali, Dover Publications, 751 fD14f 1992, ISBN 0-486-27132-3 (pbk.)

Familiar Faces - The Art of Mort Drucker, by David D, Duncan with Mort Drucker, PM 6727 D86 F3 1988, ISBN paperback: 0-941613-02-X

...Thus I say to you , whom nature prompts to pursue this art, if you wish to have a sound knowledge of the forms of objects, begin with the details of them, and do not go on to the second step till you have the first well fixed in memory and in practice. And remember to acquire diligence rather than rapidity.

Perspective

Proportions of Objects

Copy from the Master

Copy from Nature

See the works of various Masters

Get into the habit of putting his art into practice and work

"All satisfying things are good organizations. The forms are related to each other, there is a dominant movement among them to a supreme conclusion."

Henry Miller from

The Art of painting in the Twentieth Century edited by Pierre Seghers in collaboration with Jacques Charpier from Hawthorn

....draw back the curtains. How they glow in the cold light of early dawn! Another hour or two and they will already have lost some of their gleam and sparkle. Coming on them by surprise this way they give the impression of having slept all night with their eyes open.

Is there any writer who rouses himself at daybreak in order to read the pages of his manuscript? Perish the thought!

THE practice of any art demands more than mere savoir faire. One must not only be in love with what one does, one must also know how to make love. In love self is obliterated. Only the beloved counts. Whether the beloved be a bowl of fruit, a pastoral scene, or the interior of a bawdy house makes no difference. One must be in it and of it wholly. Before a subject can be transmitted aesthetically it must be devoured and absorbed. If it is a painting it must perspire with ecstasy.

THE individual who can adapt to this mad world of today is either a nobody or a sage. In the one case he is immune to art and in the other he is beyond it. (To Paint Is To Love Again)

BUT one of the moments I like best, after having done what I imagine to be my utmost, is the realization that it won't do at all. I decide to convert the quiet, static picture in front of me into a live, careless, free and easy thing. I strike out boldly with whatever comes to hand—pencil, crayon, brush, charcoal, ink—anything which will demolish the studied effect obtained and give me fresh ground for experiment. I used to think that the striking results obtained in this fashion were due to accident, but I no longer am of this mind. Not only do I Know today that it is the method employed by some very famous painters (Rouault immediately comes to mind), but, I recognize that it is often the same method which I employ in writing. I don't go over my canvas, in writing . . . , but I keep breaking new ground until I reach the level of exact expression, leaving all the trials and groupings there, but raising them in a sort of spiral circumnavigation, until they make a solid under-body or under-pinning, whichever the case may be. And this, I notice, is precisely the ritual of life which is practiced by the man who evolves. He doesn't go back, figuratively, to correct his errors and defects; he transposes and converts them into virtues. He makes wings of larval cerements. • TODAY I see that my steadfast desire was alone responsible for whatever progress or mastery I have made. The reality is always there, and it is preceded by vision. And if one keeps looking steadily the vision crystallizes into fact or deed. There is no escaping it. It doesn't matter what route one travels—every route brings you eventually to this goal. "All roads lead to Heaven," is the Chinese proverb. If one accepted that fully, one would get there so much more quickly. One should not be worrying about the degree of "success" obtained by each and every effort, but only concentrate on maintaining the vision, keeping it sure and steady. The rest is sleight-of-hand work in the dark, a genuine automatic process, no less somnambulistic because accompanied by pains and aches.

The stark lone portrait head of modern times is frightening because of its un relatedness. It is the symbol of the brain functioning in a void.

Going home in the Metro, got so interested in that bit of flesh just above the eyeball, in the spaciousness and voluptuousness of it, that I rode past my station. . . .

One day, odd as it sounds, you suddenly see what makes a wagon, for example. You see the wagon in the wagon—and not the cliché image which you were taught to recognize as "wagon" and accept for the rest of your life as a time-saving convenience. The development of this faculty, for an artist in any realm, is what stops the clock and permits him to live fully and freely. He gets out of rhythm with the crowd and in so doing he '' creates time'' to see what surrounds him. If he were moving like the others he would remain deaf and blind with them. It is the voluntary arrest that really sets him in heavenly motion and permits him to see, feel, hear, think. Eh, what? (The Waters Reglitterized)

http://www.eapoe.org/works/essays/philcomp.htm

THE PHILOSOPHY OF COMPOSITION.

———

BY EDGAR A. POE.

When composing a work, Tom creates with formulas. This treatise by Poe is similar.

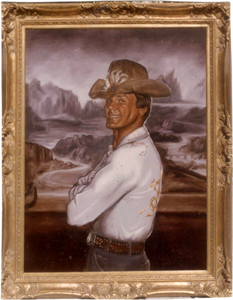

Ralph Wolfe Cowan, Oil on vinyl covered plywood, 30" x 40", 1981

While Tom was apprenticing under Ralph, he painted his portrait. Ralph loved the cowboy hat and embroidered shirt. The background is from the Mona Lisa.

201214 Pallete used for Keith Richards

The pallette Ralph used. Taught at the Art Students League in New York City.

Ralph studied there about a week before setting off on his own. He always was

a fast learner. Tom studied there about a week before leaving to help Ralph

for he had just moved to New York City after a stint in Washington DC. He was

still imbibing at the time and lived with Tom in his railroad apartment at 89

Christopher St. Tom fondly remembers giving him his last dime to make a call

to an old patron.

Tom thinks of Ralph often and always when he has a brush in his hand.

The Manner

Art is truth, beauty, order, justice and culture

The artist was twenty years old when he met his master. He had seen his large full length celebrity portraits that decorated a bar and had to meet him. The bartender pointed to a man slouched over the bar, drunk. Sitting up the master seemed rather interested in the young man. The master had a son but gave him up in a nasty divorce. Maybe the young artist, very interested in painting, substituted for his son.

The young artist had the gates of the painting firmament opened when he entered the master’s studio. Seeing the paint on the palette, the brushes, and the unfinished canvas the young artist knew instinctively what to do. Thirty years later the young artist still strives to paint smooth transparent figurative work in the manner of William Adolphe Bouguereau 1825-1905.

Initially four years of study were needed to gain the simple mastery of the technique. The master’s technique was wet on wet. He never repainted or glazed unless the first application was not good enough. His master likes to paint in the face as a mask of flesh only placing in the eyes, brows, lips after the face was formed completely finally using a Hacke brush to blend the color.

The young artist also paints the surface all at once working wet on wet. The work proceeds like a mural, applying only the plaster you can paint in a day. The young artists work starts with a simple pencil drawing. Once correct, most of the pencil is removed with a kneaded eraser or alcohol. The master likes to paint a simple line drawing of the subject with many of the details of the line revealing itself in the final surface.

The young artist applies his color in two parts. First the transparent color. The canvas provides the white and the thin veil of color creates the tone. Once the transparent color has been taken as far as it can to produce form the opaque layer is applied only in areas where it is needed to enhance the form. His master likes to use opaque color.

The young artist works on a scrapped gesso canvas. His master works on sign painter’s canvas stretched on board painted middle violet. The young artist’s method is more time consuming. Stretching heavy cotton primed canvas over board and then apply gesso with a knife. Once dry he scraps the surface with a razor blade, reapplying gesso with a knife five to ten times till the surface is very smooth with a gray patina from the razor blade he uses to scrap the gesso smooth. He uses regular oil paint mixed with very little oil of cloves to prevent it from drying and safflower oil as a medium for it long drying time. The oil of Cloves is a trick of his master. The colors they use are the same, brown madder alizarin, alizarin, WN bright red, Vandyke brown, olive green, transparent yellow ochre, Naples yellow, lemon yellow, sap green, ultramarine blue, cerulean blue, Thylo blue, ivory black, and titanium white.

The master and the young artist palette are the same, a sheet of glass. The young artist palette is a 16” x 12” single pane of glass that he keeps in a Tupperware box in the freezer when not working. The colors are arranged in up down rows with the red row on the far left, next is the green row then the yellow row followed by the blue then violet rows with the last row on the right the black row. The bottom of the rows is the light color and the top the darkest. By mixing the rows across you get variety. Most colors start as a mixture of two opposites or not so much an opposite but still a dirty clean color is the result.

Work starts on the face with laying in color with a number 4 round red sable. When the area is mostly filled in a smaller brush is used. To blend the color a used filbert sable is cut at a diagonal and used to stipple the colors together. Smaller and smaller brushes are use until all the spaces are filled in. A #1 red sable stripping brush is used for the final blending. The brush is dry and by slightly touching the brush at an angle to the surface the paint is slowly blended. Work proceeds at a steady pace for ten days while the paint is still wet.

The young artist learned that he was obsessed with the surface of the painting not so much about what is painted.

In my manner, I use a little oil of cloves in my paint to prolong the drying and therefore rework areas until they are correct. The oil is about two drops in a quarter golf ball size to prolong drying to about seven days. I work in a smooth surface manner, which means that the paint is thin on the very smooth surface of the canvas. I apply gesso to primed canvas with a palette knife applying the thinnest coatings until the surface is very smooth like the surface of Bouguereau’s canvas. A final scraping with a razor blade in the area of the face before starting work on the face gives the best smooth surface but some of the metal from the blade turns the canvas gray. If you do not scrap with a razor blade the surface is pristine white which is best. Work is done on sections of the canvas to achieve the effect I want. The rest of the surface is bare canvas with a pencil drawing or cartoon. When it comes time to paint, I remove the pencil with alcohol and cotton swabs.

My colors are Left Row top to bottom: Alizarin Crimson, Winsor Newton Bright Red; Next Row Right: Windsor Newton Vandyke Brown, Transparent Gold Ochre, Yellow Ochre, Lemon Yellow; Third Row Right: Windsor Newton Olive Green, Windsor Newton Sap Green, Thylo Green, Cadmium Green; Fourth Row Right: Thylo Blue, Ultramarine Blue, Cerulean Blue; Fifth Row Right: Dark Violet, Medium Violet; Sixth Row Right: Ivory Black, Titanium White

The colors align themselves dark to light with light at the bottom. You mix flesh by combining three pure colors. Always apply a higher croma color because just the application deadens the color.

Make several mixtures of face color,

about five. One very light and one very dark and evenly spaced tints in-between.

Then you can paint with mixed color and do the shading cleanly. You should not

try to mix the color on the paper. Using direct application of tints by themselves

will be a lot more aesthetic. In fact it would not be a bad thing to have many

colors premixed for a certain painting.

When I paint with watercolor I have about thirty little film canisters mixed

up and then can quickly paint the light pencil drawing on the paper. After I

am finished I put the caps back on and then into the freezer. I have all the

film canisters around the edge of a paint box. In the middle is some paper sheets

that mark the color that is in the canister.

View Tom

Lohre' locations of paintings painted from life

Inspiring Smiles Forever

Complete Works, Portraits, Landscapes, Still Lifes, Sculpture, Lego Artist...

Click To Sign up for auction notices or check EBTH & E-Bay

Have any Tom Lohre painting on a myriad of materials via Fine Art America

If you don't see your favorite painting request it to be offered.

Post comments on Sidewalk Shrines and Noted Icons https://www.facebook.com/artisthos/

Special Web Sites, Family Tree, Friend's Links

11223 Cornell Park Dr. Suite 301, Blue Ash, Ohio 45242